Gadwalls, medium-sized ducks, breed near wetlands in Texas and across the southern United States. Over 280 have tested positive for avian flu in Texas since 2022. Photo by Tom Koerner/USFWS (Public domain).

Since the latest U.S. outbreak began in 2021, avian influenza — or “bird flu” — has swept through livestock and wild animals, hiking market prices and raising concerns about the disease’s potential to spread between humans.

The current risk to humans remains low but could change quickly, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In wildlife, avian flu has infected and killed more species than ever before.

To stop the spread, experts say to avoid touching dead or infected birds, follow public health guidance and remove feeders in areas with avian flu cases or residences with poultry.

WHAT IS BIRD FLU?

Avian influenza is a respiratory disease that naturally occurs in wild birds.

Waterfowl and shorebirds, including ducks, geese and gulls, carry and spread a mild form of the virus but rarely become sick. Infected birds shed the virus through their saliva, mucus and feces.

Like other viruses, avian flu mutates regularly, creating new strains. Experts categorize different families of the disease as low pathogenic avian influenza (LPAI) or highly pathogenic (HPAI) based on their impact on poultry.

Low pathogenic strains are common in wild birds worldwide and cause no to mild disease in poultry. However, some strains become highly pathogenic when the disease spills into domestic flocks, causing a fast-spreading and deadly outbreak.

The current bird flu variant belongs to the H5N1 family of highly pathogenic viruses, which first appeared in farmed poultry in China in the 1990s and since evolved and circulated in birds within Eurasia and Africa.

Avian flu crossed the Atlantic with migratory birds in late 2021, sparking the first outbreak in North America since 2014-15.

“This H5 that we have circulating is very different than [the original H5N1] or even what we saw in Europe,” said Dr. Stacey Schultz-Cherry, an influenza expert at St. Jude Children's Research Hospital.

BY THE NUMBERS

In humans: 70 people in the U.S. have contracted avian flu as of March 20. Most cases were mild. The first severe case occurred in December and one person died in January 2025. Scientists are monitoring the disease and have not yet documented transmission between humans.

In livestock: 166 million poultry and 989 dairy herds have been infected.

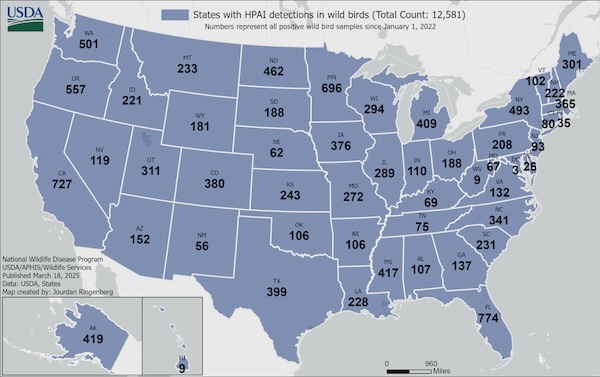

In wildlife: Avian flu has infected 12,500 wild North American birds representing over 160 species since 2022, according to the Department of Agriculture. In the last 30 days, 42 wild birds tested positive. The virus has also infected over 400 wild North American mammals from at least 27 species.

Nearly 400 wild birds have tested positive for avian flu in Texas since 2022. Image by Jourdan Ringerberg | USDA.

Nearly 400 wild birds have tested positive for avian flu in Texas since 2022. Image by Jourdan Ringerberg | USDA.

Chances of humans contracting the disease from wild birds remain low, said Megan Hahn, a regional wildlife health specialist with Texas Parks & Wildlife.

Almost all confirmed U.S. cases resulted from close contact with infected birds or contaminated environments: 41 people were exposed through dairy herds, 24 at poultry farms and culling operations and two by other animals. In three cases, the infection source is unknown.

HOW IS AVIAN FLU AFFECTING WILD BIRDS?

Whooping cranes take off along the Texas coast. Photo by Sue Ann Kendall | iNaturalist (CC 4.0).

Whooping cranes take off along the Texas coast. Photo by Sue Ann Kendall | iNaturalist (CC 4.0).

Nearly 400 wild birds have contracted avian flu in Texas. Almost all were waterfowl like blue-winged teals and gadwalls, where most detections came from hunter harvests — not disease-caused mortalities.

Recent outbreaks in Texas occurred near the Houston coastline and in Central Texas along the I-35 corridor, said Hahn.

All birds can be affected by avian flu, experts said. However, some species are more likely to be exposed to the disease or more sensitive to population declines.

Birds nesting in large flocks, especially in mixed groups with waterfowl, are at higher risk, said Hahn and Bryan Richards, emerging disease coordinator for the USGS National Wildlife Health Center.

Twenty-six colonial (or group-nesting) waterbird species nest along the Texas coast, including roseate spoonbills, brown pelicans and Caspian terns.

Birds of prey and scavenging vultures can also get sick from eating infected birds. In February, influenza killed 10 black vultures in Bexar County.

For endangered species, a bird flu outbreak could collapse populations.

After bird flu killed 1,500 sandhill cranes in Indiana earlier this year, conservationists worry their endangered relative, the whooping crane, may contract the disease.

Whooping cranes encounter large waterfowl migrations while overwintering on the Texas shoreline. With the only self-sustaining population totaling 536 birds, every individual matters for species survival.

If avian flu infects threatened populations, conservationists have few options. Current vaccines are intramuscular and require multiple doses, making wild inoculations nearly impossible. No approved treatments exist for avian flu.

However, researchers found promising signs of resistance. Some bald eagles tested positive for HPAI antibodies, indicating they survived the disease, said Richards.

AN EVOLVING DISEASE

Bird flu spillovers to other animals, including mammals, have happened before. However, this outbreak has infected more species, more often than previous epidemics.

As the H5N1 virus mutated and recombined with native low-pathogenic variants, it added more genes, expanding its range of hosts.

This variant also broke with typical seasonal patterns. Previous HPAI viruses disappeared after getting outcompeted by native low pathogenic variants in wild birds. Instead, this virus persisted, becoming endemic in Europe and North America.

In mammals, avian flu has infected carnivores that scavenge or prey on diseased birds, such as bobcats and foxes, and marine mammals that encountered migrating birds or their feces. Other species, like rodents, likely became infected after consuming raw milk from infected cattle.

Known cases in Texas mammals include seven domestic cats and a striped skunk. Photo by Jean Beaufort | Public domain.

Known cases in Texas mammals include seven domestic cats and a striped skunk. Photo by Jean Beaufort | Public domain.

So far, bird flu has not mutated in other mammals to become more transmissible to humans. However, spillovers increase the risk of the virus evolving and causing a human pandemic. Infections in species like cattle, cats and rats living near humans elevate human exposure risks.

STOPPING THE SPREAD

• Take precautions and practice good hygiene.

• Do not touch or let pets interact with sick or dead birds.

• If you must be in close contact with wild or domestic birds, wear recommended personal protective equipment.

• Wash hands thoroughly after contact with wild animals or areas frequented by birds.

• Call your healthcare provider if you feel sick after exposure to potentially infected animals.

• Avian flu can cause neurologic symptoms, where birds stumble when walking or their heads tremor or tilt, or respiratory illness including visible discharge or difficulty breathing. If a bird shows symptoms of avian flu, contact Texas Parks and Wildlife or a public health agency.

• Remove bird feeders if you own backyard poultry or if avian influenza was recently detected in your area. For questions about whether to remove your feeders, contact your local wildlife biologist.

• Clean bird feeders and baths regularly with a bleach-water solution to prevent spreading avian flu and other diseases.

• Keep cats inside. Cats are highly susceptible to bird flu.

• Be a bird ally. For birds, avian flu is one of many threats. North America has lost nearly 3 billion birds since 1970, with habitat loss thought to pose by far the greatest threat to birds, according to U.S. Fish and Wildlife.

• Removing wild birds’ habitats also increases the likelihood of disease exchange, as wildlife are crowded into smaller areas near humans and extreme densities of poultry, said experts.

• Collisions with buildings is another serious threat, caused by humans. Residents can help birds by turning out lights during migration season and adding native plants to their yards or community spaces.

“It's really going to take a One Health approach, where we're thinking about the environment, the animals [and] human health,” said Schultz-Cherry.

RELATED ARTICLES

Birds in steep decline since 1970s