Nolan Coliseum during this year's Sweetwater Rattlesnake Roundup, with vendors and (toward the back) the pits. Photo by Michael Smith.

Roundups have traditionally been glorified in Texas as part of the state's Old West heritage. But there’s one roundup in West Texas that many wildlife advocates want to see end.

The Sweetwater Rattlesnake Roundup, founded in 1958, has been dubbed the largest rattlesnake roundup in the U.S. Hosted by the Sweetwater Jaycees, the three-day event held annually in March, centers around a hunt that brings thousands of pounds of rattlesnakes to the town’s coliseum to be shown to the crowd, milked of venom, killed, skinned and fried.

Local folks claim that the roundup keeps the rattlesnakes’ numbers in check and provides an economic boost to the community. But the use of gasoline to collect them, miseducation about snakes and the celebration of the butchering of wildlife have made the event controversial.

SNAKES BY THE POUND

A Jaycee member in the process of decapitating a rattlesnake. Photo by Michael Smith.

A Jaycee member in the process of decapitating a rattlesnake. Photo by Michael Smith.

I re-visited the roundup on March 14, driving through a hazardous dust storm to reach the Nolan County Coliseum. There I watched Jaycees hook rattlesnakes out of big yellow trash cans to pin them and extract venom or position them on a tree stump to decapitate them with a machete. The show was very much like what I had seen on my first visit to the roundup in 2001.

It’s a very direct and visceral show. People in the crowd snicker when snakes thrash under the hook or when grasped without support. When a Jaycee offers a decapitated body up for someone to touch, he jokes, “He won’t bite you, I took care of that!”

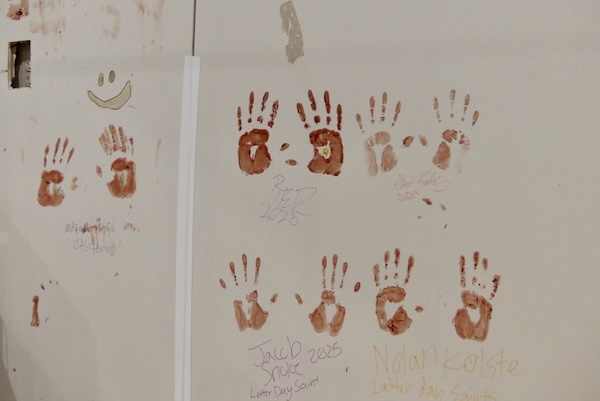

Dull red hand prints on a wall reflect people putting their hands in rattlesnake blood and then pressing them against the wall.

Participant handprints in rattlesnake blood, during the skinning and gutting. Photo by Michael Smith.

Participant handprints in rattlesnake blood, during the skinning and gutting. Photo by Michael Smith.

At Sweetwater, snake hunters profit by selling snakes for as much as $20 per pound, with cash prizes for the most snakes (by weight), the longest snake, and other incentives. The Sweetwater Jaycees who put on the event report that this year’s total weight was 3,521 pounds. Compare that with the record from 2016 when 24,262 pounds of rattlesnake were sold. Texas Parks and Wildlife Department (TPWD) reports that from 1959 to 2015, hunters brought in as many as 17,986 pounds of rattlesnakes, but the average during that time was about 5,600 pounds.

WESTERN DIAMOND-BACKED RATTLESNAKES

lncoming rattlesnakes — counted and measured — waiting to be shown, milked and killed. Photo by Michael Smith.

lncoming rattlesnakes — counted and measured — waiting to be shown, milked and killed. Photo by Michael Smith.

The focus of all this effort and controversy is the western diamond-backed rattlesnake, Texas’ biggest and potentially most dangerous venomous snake. It sometimes grows to over seven feet, but most are closer to half that length.

Its bite is always a medical emergency, but as reported by Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, “only 0.2 percent of venomous snakebites result in death”. In Texas, that’s about 1 to 2 people annually, a low mortality because most people get in-hospital treatment with antivenom.

Western diamond-backed rattlesnakes prefer fairly dry habitats such as grasslands, shrublands, rocky areas and deserts. They are found in much of Central and West Texas, a few surrounding states, and southward into Mexico. These rattlesnakes eat large numbers of rodents, benefiting farmers and ranchers. When extracted under proper conditions, their venom has medical uses, including the production of antivenom to treat snake bite.

DO ROUNDUPS PROTECT KIDS AND COWS?

Roundup promoters justify killing all those snakes by claiming that they would otherwise be “overrun” by rattlesnakes biting their kids and their cows. Venomous snakebite to any human is a terrible thing, and anyone living in West Texas has to be careful not to accidentally put their hands near one or step on it.

However, statements from at least one roundup participant actually suggested that they want to see a continuing population of rattlesnakes, presumably as an economic resource. In 2001, a participant in the “measuring pit” stated that while out on their ranches, when they find smaller rattlesnakes, they put them aside as “seed snakes” and don’t collect or kill them.

Todd Autry, who has attended roundups in many places and leads a group called “Rise Against Rattlesnake Roundups” (RARR), told me “I know several hunters who hunt in Texas and Oklahoma and they’ll alternate between den sites, they won’t take some under a certain size, and that’s part of the game, that they want to be able to go and find snakes next year.”

Miss Snakecharmer, in the process of decapitating a rattlesnake. For each roundup, a girl or young woman is selected to be "Miss Snakecharmer" for the event. Photo by Michael Smith.

Miss Snakecharmer, in the process of decapitating a rattlesnake. For each roundup, a girl or young woman is selected to be "Miss Snakecharmer" for the event. Photo by Michael Smith.

The Sweetwater roundup claims that it originated when ranchers noticed that rattlesnakes were killing their cattle (reported by Abilene news outlet KTXS). Rattlesnake bites to cattle can happen but are rare, according to an article in Beef, a publication unlikely to be biased in favor of snakes. An article in Merck Veterinary Manual also reports that large livestock seldom die. Their large body size tends to make venomous snake bite, if it occurs, less dangerous than it would be in a smaller animal like a dog.

DECLINING PASTIME?

In recent years, there has tended to be a gradual decline in the total weight of snakes brought to the Sweetwater roundup. This might be explained by a decrease in the population of rattlesnakes, fewer participants trying to find snakes, or less time and energy spent looking for them.

Might the decrease reflect a shrinking population of rattlesnakes out there? The experts I spoke with agreed that the western diamondback is a resilient species that may be doing okay despite the roundup, but no one knows for sure. The state herpetologist for Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, Dr. Paul Crump, said that there was no good scientific data on this question.

If it’s not about protecting people and livestock, why do the roundups persist? Money is one reason. The city of Sweetwater reported that the economic impact of the roundup on the local community was $8.4 million in 2015 (reported by TPWD). And this year, hunters were getting as much as $20 per pound for rattlesnakes.

VENOM FROM ROUNDUPS

A participant milking venom from a rattlesnake. Photo by Michael Smith.

Another claim by the roundup is that the venom that is extracted from snakes is sold for research and pharmaceutical uses. But if you dig a little, you find that the companies that make medicines or antivenom say that they do not use venom from roundups. BTG, the maker of Cro-Fab (the most commonly used antivenom) states that it would not knowingly use venom collected at a roundup.

I have watched Jaycees milking venom in the “milking pit,” an enclosure with walls chest high. They use a snake hook to pull a snake from one of the yellow garbage cans. The animal might be limp, perhaps from dehydration, suffocation after being buried under other snakes, or from the effects of breathing gasoline fumes.

Another claim by the roundup is that the venom that is extracted from snakes is sold for research and pharmaceutical uses. But if you dig a little, you find that the companies that make medicines or antivenom say that they do not use venom from roundups.

But if the snake has some strength, the Jaycee pins its head under the hook and grasps it just behind the jaws. The animal’s mouth, which may be bloody from injuries, is pushed against the lip of a glass funnel until it bites. The handler squeezes where the venom glands are located, toward the back of the head, and yellow venom rolls down into the funnel. The snake is then tossed aside to await its slaughter.

I spoke with Dennis Cumbie while at the milking pit. Cumbie has produced venom from roundups for some years, and he states that while pharmaceutical companies may say they don’t use venom from roundups, they actually do. He offered no evidence for this claim.

USE OF GASOLINE TO COLLECT SNAKES

Snake heads in jars offered by vendors, photographed during a power outage at the coliseum. Photo by Michael Smith.

Snake heads in jars offered by vendors, photographed during a power outage at the coliseum. Photo by Michael Smith.

As winter ends, out on the Rolling Plains the western diamond-backed rattlesnakes are often gathered in fissures and crevices far enough underground to escape freezing. Other snake species may be present, as well as lizards, turtles, and toads. Additionally, burrowing owls and ground squirrels may occupy those underground shelters. And there are insects and other invertebrates that live underground (that is, “karst” invertebrates), a number of which are listed as endangered and protected.

The typical practice for hunters collecting for the roundup is to spray either a mist or fumes of gasoline into those subterranean shelters to drive the snakes out. It generally works, but gasoline contains things like benzene and toluene that are very toxic to humans and wildlife. The potential for killing of non-target wildlife (animals other than rattlesnakes) has been a concern for a long time. This led TPWD to look into whether the use of gasoline should be allowed in the collection of snakes.

In 2013, TPWD received a petition asking the agency to prohibit the practice. The agency briefed the Texas Parks and Wildlife Commission about the issue, and the Commission directed the agency to prepare options for a rule banning gassing. A period of public comment ran from 2013 into 2014, resulting in “9,312 comments in support of the proposed rule, 743 in partial or complete opposition, and 82 offering no discernible opinion” (TPWD Snake Harvest Working Group Reference Documents).

However, because of political opposition, in May of 2014 the directive was to table the rule and form a “Snake Harvest Working Group” (SHWG) that would be composed of stakeholders representing the points of view of snake hunter and roundup folks as well as biologists and wildlife professionals. The SHWG met four times, presenting recommendations to TPWD in 2015.

At the time, John Davis was Wildlife Diversity Program Director for TPWD and was appointed to be the agency’s resource staff for the SHWG. He is now retired from TPWD, and I spoke with him about the gassing issue.

“The Texas Parks and Wildlife Commission was going to implement the regulation,” Davis said. While it’s true that the Snake Harvest Working Group (SHWG) did not reach a consensus or unanimous conclusion, there were majority conclusions. Davis said, “The majority perspective was that what TPWD was attempting to do made sense.”

The Commission had listened to the SHWG and to the public comments and were in favor of the regulation. However, Davis told me that a phone call from an influential Texas legislator brought pressure to bear so that TPWD elected to table the gassing rule indefinitely.

“At this point there is not enough support from either the community or legislative oversight for the department to move forward with regulating the use of gasoline to collect rattlesnakes,” he said.

In 2013, TPWD received a petition asking the agency to prohibit gassing of rattlesnakes. The agency briefed the Texas Parks and Wildlife Commission about the issue, and the Commission directed the agency to prepare options for a rule banning gassing. Nearly 10,000 public comments were in support of the ban, with less than 750 opposing it. However, TPWD tabled the gassing rule indefinitely after a phone call from an influential Texas legislator, according to John Davis, Wildlife Diversity Program Director for TPWD.

So what happened to the practice of gassing snake dens? RARR’s Autry said, “I know a lot of people in Texas still do, and Oklahoma watches out for it and any roundup in Oklahoma will not buy gassed snakes. I’ve seen snakes in Oklahoma rejected from sale because they thought they’d been gassed.” He went on to say, “Oklahoma has outlawed it, and I’ve never seen an Oklahoma hunter gas.”

At Sweetwater this year, in the “skinning pit” I spoke with Red Hurd II. He said “A lot of people have the misconception that we’re pouring liquid gasoline into the dens, and that’s not the case whatsoever. In a regular weed sprayer, we remove the tube that goes all the way to the bottom, so whenever we’re actually ‘gassing,’ what it’s getting is nothing but the vapors.” He described that in addition to rattlesnakes, they may see various mammals including porcupines or rabbits come out of the burrow or crevice.

According to SHWG documents, some hunters do spray a mist of liquid gasoline into these winter refuges. But both mist and fumes are toxic and often deadly. In a study from 1989, Dr. Jonathan Campbell and colleagues examined how western diamond-backed rattlesnakes as well as rat snakes, kingsnakes, racers (a snake species), collared lizards, Woodhouse’s toads, and house crickets responded when exposed to gasoline fumes. Rattlesnakes exposed to fumes were neurologically impaired for a time and all but one appeared to recover. Other species of snakes were more severely affected and several died. Toads and crickets exposed to fumes for as much as 30 minutes died (Campbell, et al., 1989, Texas Journal of Science).

While the TPWD regulation was not implemented, the SHWG produced valuable information that anyone can access. There’s an Executive Summary, a Final Report, but even more importantly there is something called “Reference Documents.”

Davis told me, “Every time I talk to someone, I say ‘don’t read the final report, read the Reference Documents — that’s got all the stuff in it.’”

These are not lists of references, it is the complete story, thorough but not difficult to read.

SLAUGHTERED, SKINNED AND EATEN

A serving of fried rattlesnake at the roundup. Photo by Michael Smith.

After being looked at, kicked around, milked, and offered to audience members to touch while the Jaycee held their heads, there was one more step awaiting the rattlesnakes at the roundup. A yellow garbage can with multiple snakes would be carried to the “skinning pit” where each one was pulled out with metal tongs and its head positioned on a tree stump. A Jaycee then decapitated the snake with a machete. The snake’s head was unceremoniously dumped into a trash can and the writhing body hung over a butchering table to be skinned.

Someone asked whether the decapitated snake was now dead, and the Jaycee said that it was dead at the moment of decapitation. However, at the roundup 24 years ago Carl Franklin and I monitored the decapitated heads for at least 15 minutes. During that time, heads responded to being bumped by trying to writhe away or turning to try to bite the newcomer. We know that nerve circuits continue to fire for a time after death, but this looked like some lingering life.

Could the low reptilian metabolism mean that the snake’s head took at least several minutes to die? Page 93 of the American Veterinary Medical Association Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals: 2020 Edition notes that the central nervous system of reptiles and amphibians is tolerant, for a time, of oxygen deprivation and low blood pressure. Accordingly, they recommend that to humanely kill a reptile, its brain should be destroyed (pithed). And so it appears that those severed heads may not immediately die.

The snakes are skinned and some of the meat is cooked on-site (while the rest is sold). Many of us have wondered about the potential for gasoline-contaminated meat being eaten. John Davis told me that with agricultural animals like cows, there is a process for keeping track of what the animal has been exposed to, in order to protect health. However, with wildlife such as rattlesnakes, “there are no rules for what happens to the meat before slaughter. It’s like a USDA no man’s land.”

THE FUTURE OF ROUNDUPS

Groups such as Rise Against Rattlesnake Roundups have proposed that roundups should be managed so that their activities do not threaten wildlife (including wild populations of rattlesnakes). They would like to see roundups become more like the Whigham Rattlesnake Roundup in Georgia which now uses captive snakes, does not kill them, and focuses on education. But Sweetwater has not indicated an interest in becoming a “no-kill” event.

It is also possible that the old-style roundups are dying out. Todd Autry said, “In 1981 in the book Texas Rattlesnake Roundups there were 44 hunts in Texas and today there are only 4 or 5 left.” He went on to say, “It’s not being passed along to the younger generation, not like it was.”

If they ever did change, abandon the poisoning of wildlife with gasoline, and leave behind the performative cruelty, a lot of us might join the folks of Sweetwater each year for a much more joyful event.

RELATED ARTICLES

Shaking out the facts from fiction about rattlesnakes

How to avoid a snake bite and what to do if you get bit

Snake ID takes practice, cautions North Texas expert

Western rat snakes can spook North Texas homeowners

Cottonmouths have been miscast in tall tales, says Arlington expert